Write something

The Origin Story: Apples, Phlorizin, and Glucose Wasting

My friend and colleague @Brian Graham was actually the one who first mentioned that SGLT2 inhibitors trace their roots back to apples. I love stories like this where science and trivia overlap so I dug in to learn more and wanted to share what I found. Big thanks to Brian for sparking the curiosity and inspiration behind this one. In the 1830s, chemists isolated a natural compound from apple tree bark (and to a lesser degree from the apple itself) called phlorizin (also spelled phloridzin). It’s a glucoside of phloretin, part of the polyphenolic family that gives apples some of their antioxidant and metabolic effects. Researchers later discovered that when animals or humans were given phlorizin, they started excreting large amounts of glucose in their urine even though their blood glucose wasn’t dramatically elevated. This was puzzling, because under normal physiology, the kidneys reabsorb nearly all filtered glucose in the proximal tubule to prevent energy loss. That phenomenon glucosuria without hyperglycemia was the first clue that the kidneys had a specific glucose transport mechanism that could be pharmacologically blocked. By the mid-1900s, scientists identified that glucose reabsorption occurs through sodium-glucose co-transporters (SGLTs), primarily SGLT2 in the proximal tubule (responsible for ~90% of glucose reuptake) and SGLT1 further downstream. Phlorizin turned out to be a competitive inhibitor of both SGLT1 and SGLT2, preventing glucose reabsorption and causing its excretion. However, phlorizin itself wasn’t a good drug it was poorly absorbed orally and was rapidly hydrolyzed in the intestine to phloretin, which blocked other transporters nonspecifically and caused GI issues. So, researchers asked: Could we make a stable, orally bioavailable derivative that selectively blocks SGLT2? That question directly led to the modern SGLT2 inhibitor class. Medicinal chemists used the phlorizin scaffold as the blueprint, modifying the C-glucoside linkage (to resist enzymatic cleavage) and tweaking ring structures to increase selectivity for SGLT2 over SGLT1.

KetoneAid and Sleep

hey all. Wondering if anyone else is experiencing similar. I find sometimes when I take ketoneaid in the evening (around 5pm-7pm) I have trouble sleeping (usually Go to bed ariund 1030 or 11 but in those cases can’t fall asleep well past midnight/1am). Am only taking 2.5grams. One change to potentially make is to only Take it before noon as an example but am wondering if perhaps it’s a false positive signal given the quantity is low at 2.5 grams and the effect seems to be lasting way too long? Interested to hear any anecdotes folks may have.

0

0

Choosing The Right Ketone

I get asked often about why I am so partial to Kenetik Pro or Ke4 over other forms of ketones. I thought I would do a short primer on this topic to help everyone better understand. 1. Delta G (D-BHB only) D-β-hydroxybutyrate in powder or liquid form. Instant BHB in your blood—peaks ~1–2 mM in 30–60 min. Fast energy for brain and muscle, but levels crash back by 2–3 hrs. No extra fuel source once it clears. 2. Ketone IQ (1,3-Butanediol only) 1,3-butanediol (BD) that your liver turns into D-BHB.• Metabolism: BD → alcohol dehydrogenase → D-BHB over 1–4 hrs. Peak ~1.5–2 mM. Slower, lower ketone rise; minimal GI issues or electrolytes—but no immediate spike, so it can feel underwhelming. 3. Medium-chain triglycerides (C6–C10 fats).• Metabolism: Goes straight to liver, β-oxidized to acetyl-CoA, then partially converted to BHB over 2–4 hrs. Peak ~0.3–0.6 mM.• Effects: Gentle, sustained mild ketosis. But high doses (>30 g) often cause cramps, diarrhea, and only low-level ketones. 4. Dual Ester (Kenetik Pro or KE4: D-BHB + 1,3-Butanediol in one molecule) A single compound that, when digested, releases free D-BHB immediately AND 1,3-BD for later conversion.Immediate D-BHB spike to ~3–5 mM in 30–60 min.– 1,3-BD portion converts to more D-BHB over the next 2–4 hrs, sustaining levels at ~2–3 mM for 4–6 hrs.– No mineral load, neutral pH, minimal gut upset. Dual-phase ketonaemia—fast AND long.– Trains your own ketone-burning machinery (upregulates BDH1/SCOT).– Clean fuel with zero electrolyte drama and near-instant mental/physical boost. The reason I choose the Kenetik Pro or Ke4 is because with the combination of fats + sustained you get a turbo-boost spike AND a steady cruise, all from one dose.They are clean with no sodium/potassium dump like salts, no stomach revolt like high-dose MCT.They leave blood pH and electrolytes untouched Using them regularly improves your cells’ ability to burn ketones long-term. These are the staple of my supplementatoin. If you want the highest, quickest, and longest-lasting ketone lift—without cramping, gut issues, or electrolyte headaches—grab the dual-ester formula (Kenetik Pro or KE4). It’s simply the gold standard for peak performance, brain power, and metabolic flexibility. If your interested in learning more about them I highly recommend the book 4th Fuel by Travis Kristofferson. Do you use Ketones? Which ones?

Your Muscles and Brain Aren’t Breaking — Their Membranes Are

Most people think of seafood as “protein plus omega-3s.” That framing is incomplete. What actually makes marine foods unique is not just the fats they contain, but how those fats are organized inside membranes. This organization happens through phospholipids, and phospholipids determine how cells breathe, signal, contract, recover, and adapt. If you want to understand muscle performance, brain health, recovery, inflammation, or aging, you have to understand membrane biology first. This article will walk through what phospholipids are, why membranes matter more than isolated nutrients, and how mussels, mackerel, sardines, and anchovies differ at a molecular level. We’ll move from beginner-friendly analogies to mitochondrial signaling and redox chemistry, and end with clear takeaways for clinicians and strength coaches. Start with a simple picture. Every cell in your body is wrapped in a membrane. Every mitochondrion inside that cell is also wrapped in membranes. These membranes are not passive walls. They are active, dynamic surfaces where energy transfer, signaling, and adaptation happen. The material those membranes are made of determines whether signals flow cleanly or break down into noise. Phospholipids are the structural units of membranes. Each phospholipid has a “head” that interacts with water and “tails” that interact with fat. When billions of them line up, they form a flexible, semi-fluid surface that proteins, receptors, enzymes, and ion channels embed into. If the phospholipid composition is poor, those proteins still exist, but they don’t work properly.A useful analogy is a racetrack. The engines (mitochondria) and drivers (enzymes) matter, but if the track surface is cracked or unstable, performance suffers no matter how strong the engine is. Phospholipids are the track surface. There are several major classes of phospholipids relevant to human physiology. Phosphatidylcholine (PC) provides membrane structure and transport. Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) contributes to curvature and mitochondrial dynamics. Phosphatidylserine (PS) is critical for signaling, especially in neurons and muscle activation. Then there are plasmalogens, a special subclass with a unique chemical bond that gives them antioxidant and redox-buffering properties.

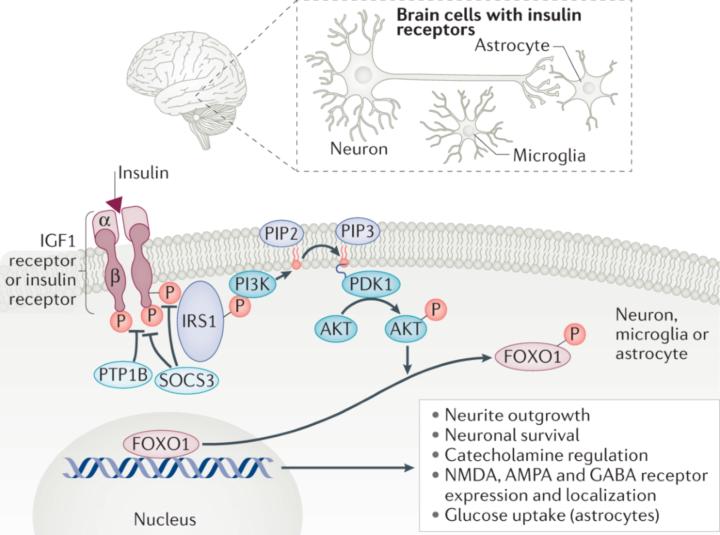

You’re Fit, Lean… and Foggy? The Hidden Form of Insulin Resistance No One Is Talking About.

Thanksgiving has a way of slowing life down just enough for you to actually notice what’s been happening underneath all the noise. You sit with people you love, share a big meal, breathe for the first time in weeks, and suddenly you’re able to feel things you usually ignore. Maybe this year, in that moment of stillness, you noticed something strange: your body feels strong, your training is dialed in, your glucose looks perfect… but your brain doesn’t match how good the rest of you feels. Maybe you felt foggy after a meal, mentally slower than usual, overwhelmed for no reason, or just “not as sharp,” even though everything on paper says you’re metabolically healthy. If that sounds familiar, you are not alone and there’s a real physiological explanation behind it. How can someone be physically insulin-sensitive yet mentally sluggish? How can your muscles get the fuel they need while your brain feels like it’s running on fumes? This article is written for you, to answer exactly that question. Central insulin resistance is the phenomenon where your brain becomes insulin-resistant even when the rest of your body remains highly insulin-sensitive. Many people experience this as a strange mismatch: they feel physically strong, metabolically healthy, and steady during training, yet their cognition feels foggy, slow, unpredictable, overwhelmed, or “under-powered.” This article explains why that happens, what the mechanisms are, how to recognize the patterns, and how to fix them, using simple language without sacrificing the biochemical accuracy that clinicians and experts expect. The first thing to understand is that the brain handles insulin differently from the rest of the body. Your muscles and liver respond directly to insulin in the bloodstream. The brain does not. For insulin to have any effect in the brain, it must cross the blood–brain barrier, bind to receptors on neurons, activate the PI3K-Akt pathway, and allow neurons to take up and use glucose. If anything disrupts that sequence, neurons will be under-fueled even if the entire rest of the body is functioning perfectly. This is why someone can have excellent fasting glucose, low insulin, perfect CGM curves, and still feel terrible cognitively. The brain can become insulin-resistant before the body gives any signal.

1-14 of 14

skool.com/castore-built-to-adapt-7414

Where science meets results. Learn peptides, training, recovery & more. No ego, no fluff—just smarter bodies, better minds, built to adapt.

Powered by