Activity

Mon

Wed

Fri

Sun

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

Jan

Feb

Mar

What is this?

Less

More

Memberships

5-Day Lead Gen Challenge

588 members • Free

Castore: Built to Adapt

812 members • Free

7 contributions to Castore: Built to Adapt

Protocol help

Hey gang Wanted to ask advice So I have focused on a protocol to deal with my OID overactive immune disorder) I’ve got hashis and CIRS … lived in mold for years without knowing… now I’m 50 and in peri menopause. I had made some nice improvements but the last few months I hit a roadblock and things have gone sideways. Extreme exhaustion, air hunger, headaches, night sweats, dizziness and wooziness , rapid weight gain, increase in hunger that’s not normal… lots of eye and nose crunchies… I have been using TA1 for like 3 months… Amantadine, rapamycin… I take LDN… I realize many symptoms could be hormonal and peri menopause … I’ve used csm to treat the mild and toxins … I’ve got VIP and am waiting to use it until my recent Marcons re-test comes back … I want to use peptides to assist in repairing mitochondria..Ive researched a decent amount and have read frequently that there’s a peptide stack for peri : 2.5 mo protocol: • Reta - 0.5-1mg/wk • Mots-C. -5-10mg/wk • Bpc157 - 0.5-1mg daily • NAD+ - 15-50mg daily Curious thoughts and suggestions if anything has worked for anyone or your clients. Thanks for any input

2

0

How One Tiny Cellular Breakdown Can Collapse Your Entire Musculoskeletal System

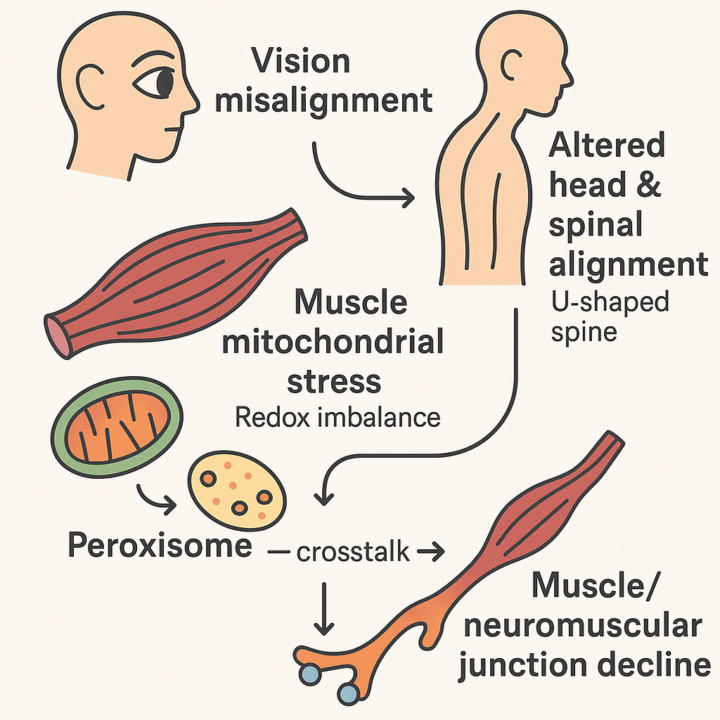

Understanding how the body maintains alignment, strength, and resilience requires going far deeper than muscle fibers and joints. Beneath posture, performance, and even the way your spine organizes itself is a constant conversation between organelles inside your cells. When this conversation is healthy, your muscles contract with precision, your nervous system communicates clearly, and your body adapts to load like it was designed to. When this communication breaks down, you see the earliest signs long before symptoms arise: slower recovery, stiffness, compensation patterns, declining power, creeping fatigue, and eventually structural breakdown. To understand why this happens, and how vision and alignment fit into the equation, you have to understand mitochondria, peroxisomes, and the quality-control systems that keep them synchronized. Imagine mitochondria as the electrical grid of every muscle cell. They convert nutrients into a flow of electrons, and that flow becomes ATP, the energy currency every cell runs on. But just like a power plant depends on transformers, regulators, and maintenance crews, mitochondria depend on other organelles, especially peroxisomes, and on their own internal quality-control systems. Peroxisomes are tiny organelles whose job is to manage specific fats, detoxify harmful metabolites, and assist in shaping the lipid membranes that make mitochondrial structure possible. If mitochondria are the power stations, peroxisomes are both the substation and the fire department. They prepare certain fuels so mitochondria can use them, and they handle the dangerous sparks before a fire spreads. A Nature Communications paper showed what happens in muscle when peroxisomes stop functioning properly. The researchers removed a single protein (Pex5) that allows peroxisomes to import the enzymes they need to do their work. Without that, peroxisomes turn into empty shells peroxisomal ghosts. Even though mitochondria were still present, their structure rapidly began to degrade. Their inner folds, called cristae, lost shape. Fuel processing became inefficient. Lipids that normally would have been handled safely accumulated and created stress signals. Over time, this metabolic and structural stress traveled outward to affect the neuromuscular junction the connection between nerves and muscle fibers and then to the muscle structure itself. The result was weakness, faster aging of the muscle, impaired recovery, and early decline of force production. What this teaches is profound: muscle dysfunction starts long before muscle fibers fail. It begins at the level of organelle-to-organelle cooperation.

The Hidden Switch: Why Long COVID Lingers and How to Restart the System 5

The final domino in long COVID recovery is integration. By now it is clear that no single pill, peptide, or supplement can resolve the condition. The problem is systemic a stalled cell danger response that traps immune, mitochondrial, vascular, and autonomic systems in alarm mode. The solution is not to throw everything at once but to restore order through a phased, feedback-driven protocol. Sequencing matters more than stacking. Just as you would not rebuild a storm-damaged city by opening shops before fixing power lines, recovery requires careful order: stabilize first, repair second, retrain third. Phase one is the redox reset and immune modulation stage. The goal here is to calm the storm and stabilize energy so the system is ready to heal. This is where Kenetik Pro becomes uniquely powerful. As a ketone monoester, it rapidly raises circulating beta-hydroxybutyrate, giving mitochondria an immediate alternative fuel. Ketones bypass damaged Complex I and glycolysis bottlenecks, providing steady ATP even when glucose metabolism is impaired. This takes pressure off fragile mitochondria, lowers lactate buildup, and gives patients the first taste of metabolic stability. Beyond energy, ketones act as signaling molecules suppressing the NLRP3 inflammasome, reducing oxidative stress, and stimulating mitochondrial biogenesis through PGC-1α. In practice, Kenetik Pro is like plugging in a backup generator during a blackout: the lights come back on, even while the grid is still being repaired. This metabolic cushion makes all other Phase 1 interventions more effective. Alongside Kenetik Pro, mitochondrial-targeted peptides like SS-31 stabilize cardiolipin and reduce electron leak. Thymic peptides such as TA-1 help restore T cell balance. KPV and resolvins modulate mast cells and push inflammation toward resolution. Antioxidant stacks with NAC, glycine, and glutathione rebuild redox buffering. Methylene blue also fits into this phase, but its timing is particularly relevant. While it can act as an electron bridge across damaged complexes, methylene blue also inhibits nitric oxide synthase. That means it can block endothelial nitric oxide production. In situations where NO is excessively high such as during oxidative stress surges, vasoplegia, or inflammatory storms this can be useful to prevent further vascular damage. But nitric oxide is not purely harmful; the immune system requires inducible nitric oxide (iNOS) to kill pathogens and regulate immune responses. If methylene blue is overused or given at the wrong point, it can blunt immune clearance and stall recovery. The art is in using it as a short-term stabilizer, not a continuous intervention. Think of it as temporarily shutting off a fire hydrant when the streets are already flooded, but making sure not to cut water supply to the firefighters who still need it.

MOLD, CIRS, VIP and other options. Would love input

Hi I’m carey. Here’s the “ short story”. Hashimotos in 2015. Terrible reaction to the vax in 2021. Didn’t want it but felt forced. Since then health worse and worse. Discovered high mmp9 and htgfb that lead me to test mold. Came back in house and in body. HLA told me I’m double copy reactive to mold, CIRS and endotoxins. Allso double mthfr and slow comt. Currently going cholastyrimine for CIRS/mold. Removed from bad air and remediated. Next is BEG spray as I’m positive for Marcons. Also positive for actinos in skin. It’s a mess. VIP peptides are on the horizon. I’m currently doing bpc 157. Next will be thymosin alpha 1. Wanted to ask about VIP and whatever else I should consider with peptides. Need to assist body in detoxing mold, endotoxins, Marcons… assist mitochondria which has been destroyed. Also curious if there would be a preferred order of taking them or stacking them. Mostly looking at Thymosin Alpha, MOTS, Epitalon, Lorazitide, and VIP. VIP is basically a certainty as it’s part of the shoemaker protocol. Thanks for reading this far! 🙏

Welcome! Introduce yourself + share a pic of your workspace 🎉

👋 Hi, I’m Anthony Castore, SSRP Fellow, Strength Coach, and one of the few bridging elite performance with cutting-edge cellular medicine. With a background in peptide sciences, mitochondrial medicine, and advanced protocol design, I’ve helped high performers—from athletes to complex medical cases—reclaim their health, build unstoppable strength, and align biology with ambition. My work fuses rigorous science with real-world application—no fluff, no hype, just results. 🔑 Why This Community Exists This isn’t just my community—it’s yours. This is your training ground. Your lab. Your launchpad. Whether you’re here to optimize body composition, repair your gut, understand redox signaling, or finally crack the code on sustainable performance—this platform is built to empower you. The goal is simple:To help you become the star of your own story—and to equip you with the tools, knowledge, and frameworks to make clear, informed decisions rooted in science, lived experience, and real-time feedback. 📚 What You’ll Get Inside • Education that scales – From beginner-friendly breakdowns to advanced protocols rooted in systems biology and peptide pharmacology.• Discussion zones – Ask questions, share insights, and get direct input on supplementation, case studies, protocol design, and training periodization.• Office hours & mentorship access – Learn how the world’s top strength coaches and cellular medicine experts think, assess, and prescribe.• Ongoing content drops – Webinars, presentations, toolkits, and behind-the-scenes of real-world cases.• A true community – This isn’t a passive group. It’s an ecosystem of thinkers, doers, and seekers—supporting each other, growing together. 🚀 My Vision To build the most trusted education platform in performance medicine—one that empowers sovereign individuals to own their biology, train with precision, and age with intention. Not just to optimize, but to understand.Not just to do more, but to do better.And not just to follow protocols—but to design your own future with clarity and confidence.

1 like • Aug '25

Hello everyone I’m Carey. I’m a personal trainer of many years and because an integrative health practitioner after being diagnosed with Hashimotos in 2015. This came a a big shock to me as I’ve been a life long athlete and Into wellness my whole life. Since then I’ve come to learn I’ve got CIRS and mold toxicity. On a mission to reclaim my health and find a new and improved way to live and learn and grow as much as possible. I have a 10 year old son and 5 year old daughter. Live in Chicago. Super excited to be here, share, and learn.

1-7 of 7

Active 21h ago

Joined Aug 1, 2025

Powered by