Activity

Mon

Wed

Fri

Sun

Jan

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

What is this?

Less

More

Owned by Nick

Pain Excellence Programme. A place to build knowledge and apply in the real world. Therapy progression REAL cases with REAL results.

Memberships

13 contributions to Pain excellence programme

Prevalence of Back Pain in UK Adults Aged 40–70 and Evidence-Based Therapy Outcomes

Prevalence - Low back pain is highly prevalent in UK adults aged 40–70, with ~25–30% reporting back pain within any given month. - Prevalence peaks in the early 50s, but remains consistently high through age 70. - Chronicity increases with age, leading to higher rates of persistent or recurrent symptoms in this demographic. Therapy Outcomes Exercise & Physiotherapy - Structured exercise programmes provide small to moderate improvements in pain and functional ability. - Best outcomes occur with supervised or group-based programmes and good adherence. - Exercise is consistently more effective than passive modalities. Psychological Interventions - CBT and ACT show strongest benefit when combined with physical rehabilitation. - Improvements are seen mainly in function, coping, and reduction in disability, rather than pain intensity alone. - Particularly valuable for chronic, non-specific low back pain. Manual Therapy - Provides short-term symptom relief for some patients. - Evidence supports its use as an adjunct, not a stand-alone treatment. - Most effective when it facilitates active rehabilitation. Interventional & Surgical Options - Injections: May benefit radicular or facet-related pain short term, but limited long-term impact. - Surgery: Most beneficial when a clear structural cause exists (e.g., radiculopathy, stenosis). Clinical Perspective - Adults aged 40–70 represent a high-burden group for persistent back pain. - Evidence supports a multidisciplinary, biopsychosocial approach combining education, exercise, behavioural strategies, and expectation management. - No single modality is curative; best outcomes occur when interventions are integrated and sustained. References 1. MacFarlane GJ, Beasley M, Jones EA, et al. The prevalence and management of low back pain across adulthood: results from a population-based cross-sectional study (the MUSICIAN study). Pain. 2012;153(1):27-32. DOI:10.1016/j.pain.2011.08.005 PubMed+1 2. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. NICE guideline NG59. Published 30 Nov 2016, updated Dec 2020. Nice+2NCBI+2 3. Singh V, Parslow D, Smith R, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy of physiotherapy interventions for low back pain. PMCID: PMC7934127. PMC 4. Tran TH, Schmitt Y, Deldon K, et al. Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy combined with physical therapy in patients with chronic low back pain. PMC article. PMC 5. Leung T-W, Chung R, Ma Y, et al. The effect of cognitive behavioural therapy on pain and disability in chronic non-specific low back pain: a systematic review. PLOS One. PLOS 6. NIHR Evidence. Cognitive behavioural therapy may help people with persistent low back pain. NIHR alert. NIHR Evidence 7. O’Keeffe M, Hayes S, O’Sullivan P, et al. Individualised cognitive functional therapy compared with a combined exercise and manual therapy intervention for chronic non-specific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial.BMJ Open. 2015;5(6):e007156. BMJ Open 8. Miki T, Kamper SJ, Roussel NA, et al. The effect of cognitive functional therapy for chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BioPsychoSocial Medicine. 2022. BioMed Central 9. Rushton A, Heneghan NR, Heymans MW, et al. Clinical course of pain and disability following primary lumbar discectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. European Spine Journal. 2020;29:1660–1670. Springer Link 10. Liu C, Tabaković I, Szetajnković M. Surgical versus non-surgical treatment for sciatica: systematic review. BMJ. 2023. BMJ 11. NHS / Local policy: Cheshire & Merseyside NHS. Spinal decompression for low back pain & sciatica policy. (Cites NICE NG59 for surgical selection.)

2

0

Happy Monday, everyone! 🌞

There’s something powerful about the start of a new week—it's a reset button, a clean slate, and an opportunity to step forward with renewed energy. Mondays get a bad reputation, but the truth is, they’re one of the best days to realign with your goals, revisit your progress, and recommit to the path you're on. Last week, each of us made progress in our own unique way—big steps, small wins, moments of clarity, or even lessons learned from challenges. All of it counts. All of it builds momentum. And today, we get to add to that momentum with intention and purpose. As we step into this new week, let’s take a moment to check in with ourselves: ✨ What’s driving you this week?Is it a personal goal you're excited to move closer to?A mindset shift you’re working on?A habit you're building—or breaking?Maybe it's simply the desire to show up for yourself a little better than you did yesterday. Whatever it is, sharing it can create connection, motivation, and support for others in this community who may need a spark of inspiration. Your story, your focus, or even your challenges could be exactly what encourages someone else to keep going. So drop your “why” for the week in the comments. 👉Let’s lift each other up, celebrate the wins ahead, and make this Monday—and this entire week—something we’re proud of. Here’s to growth, intention, and showing up. 💛🌱✨

1

0

The Soleus Muscle: A Foundational Contributor to Locomotion and Running Efficiency

Among the triceps surae group, the soleus remains one of the most underappreciated muscles in clinical and performance discussions. While the gastrocnemius often receives primary focus for its visible contribution to plantarflexion and sprinting, the soleus — with its endurance-oriented fiber composition and unique mechanical role — is arguably the first major muscle group to engage in the kinetic chain during gait initiation and running. Anatomical and Functional Overview The soleus originates from the posterior aspect of the tibia and fibula and inserts into the calcaneus via the Achilles tendon. Unlike the gastrocnemius, it does not cross the knee joint, allowing for consistent activation regardless of knee angle. This monoarticular design enables the soleus to provide postural stability and generate sustained plantarflexion torque, particularly during stance and propulsion phases (Michaud, n.d.). The muscle’s composition is predominantly Type I slow-twitch fibers, making it highly fatigue-resistant and capable of sustaining prolonged contraction without rapid decline in force output (Böhm et al., 2021). This structural adaptation is critical for its continuous role in stabilizing the tibia over the talus and maintaining center-of-mass control throughout gait. Early Engagement and Mechanical Role in Gait During the stance phase of both walking and running, the soleus is among the first lower-limb muscle groups to engage following heel contact. It eccentrically controls tibial advancement over the foot, then transitions concentrically to provide propulsive force. Research using ultrasound and EMG data confirms that the soleus fascicles remain active throughout stance, operating near optimal shortening velocities for mechanical efficiency (Böhm et al., 2021; Lai et al., 2015). In running, this function becomes magnified. Sasaki and Neptune (2006) demonstrated that the soleus contributes substantially to both vertical support and forward propulsion, generating forces up to eight times body weight at push-off. These mechanical contributions occur with minimal metabolic cost due to its fiber type composition and tendon elasticity, highlighting its role in energy conservation during repetitive loading cycles.

1

0

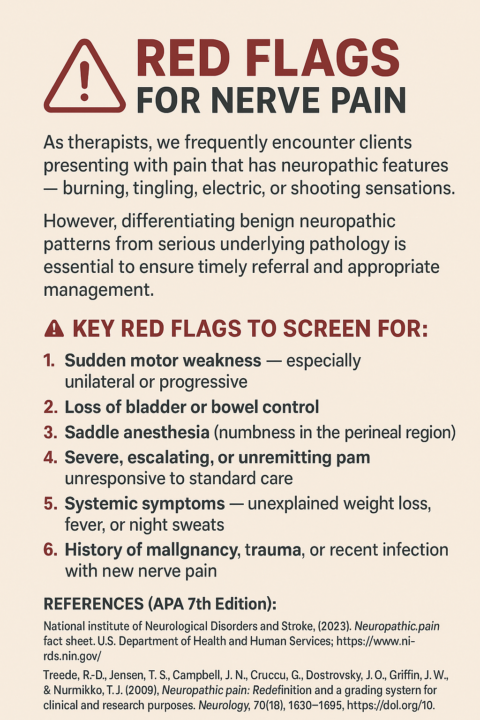

🧠 Recognising Red Flags for Nerve Pain in Clinical Practice 🚨

When these signs are present, immediate medical assessment is warranted to rule out conditions such as cauda equina syndrome, spinal cord compression, or systemic infection. As movement and rehabilitation professionals, our role isn’t only to alleviate pain but also to recognize when neurological compromise requires escalation. Early identification can significantly reduce morbidity and improve outcomes for our clients. 📚 References (APA 7th Edition): - National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2023). Neuropathic pain fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/ - Treede, R.-D., Jensen, T. S., Campbell, J. N., Cruccu, G., Dostrovsky, J. O., Griffin, J. W., & Nurmikko, T. J. (2008). Neuropathic pain: Redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology, 70(18), 1630–1635. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000282763.29778.59 - National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2020). Neuropathic pain in adults: Pharmacological management in non-specialist settings (CG173). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg173

2

0

The Power of Multi-Directional Low-Level Isometric Rehab 💪

With musculoskeletal rehabilitation, multi-directional low-level isometric training represents a critical early-phase intervention strategy aimed at restoring neuromuscular control, reducing pain, and re-establishing joint stability before progression to higher-load dynamic tasks. 1. Neuromuscular Re-educationLow-intensity isometric contractions (typically <30% MVC) facilitate cortical and spinal motor pathway activation without imposing excessive joint stress. Research demonstrates that early-stage isometrics can help reverse arthrogenic muscle inhibition, particularly following injury or surgery, and re-establish efficient motor unit recruitment patterns (Hopkins & Ingersoll, 2000; Rice & McNair, 2010). 2. Multi-Directional Load ToleranceBy applying controlled isometric contractions across multiple planes, clinicians can progressively expose the musculoskeletal system to variable force vectors. This approach enhances proprioceptive input and improves joint stability by training co-contraction and force modulation capacities in different directions — essential for restoring functional resilience (Frank et al., 2015; Crossley et al., 2020). 3. Pain Modulation and Tissue ProtectionSub-maximal isometric work can activate descending inhibitory pathways and reduce pain perception, providing an analgesic effect without aggravating tissue load. This supports early engagement in rehabilitation and maintains muscle activation during phases of limited mobility (Rio et al., 2015; Rio et al., 2016). 4. Progressive Framework for Load IntegrationMulti-directional isometrics serve as a bridge between passive therapy and dynamic strengthening. They establish a baseline of load tolerance and coordination, creating the foundation for progressive isotonic and plyometric phases (Behm & Sale, 1993; O’Sullivan et al., 2012). In summary, multi-directional low-level isometric rehabilitation is a highly effective evidence-based method for early-stage recovery. It promotes neuromuscular reactivation, modulates pain, and builds directional stability — key components for optimal long-term outcomes in both athletic and general populations.

2

0

1-10 of 13

@nick-taylor-4811

Clinic owner | rehab specialist | mentor . 300+ elite athletes & 2500+ private clients helped with my step-by-step structured system to approach pain

Active 14d ago

Joined Oct 28, 2025