Write something

The Preserve Profile: Engineering a "Sticky-Bark" Hybrid

Most pitmasters use a binder just to make the salt and pepper stick. But when you use jam, you are introducing two powerful culinary agents: High-Concentration Fructose and Pectin. 1. The Pectin "Glue" Pectin is a naturally occurring polysaccharide found in the cell walls of fruits. In jam making, it’s what causes the liquid to "set" into a gel. - The BBQ Effect: When smeared on raw meat, pectin acts as a high-viscosity adhesive. It creates a thicker "film" than mustard. This allows you to apply a much heavier coating of coarse black pepper or granules without them falling off during the first hour of smoke. - Smoke Adhesion: Because pectin stays tacky for longer than water-based binders, it captures more smoke particulates (the aerosols that carry flavor) before the surface eventually dries out. 2. Differential Caramelization Standard table sugar (sucrose) begins to caramelize at roughly 160C. However, the fructose found in fruit jams begins to caramelize much lower, around 110C. - The Benefit: Since most low-and-slow BBQ happens between 107C and 135C, the fruit sugars in the jam are undergoing a slow, deep caramelization for the entire duration of the cook. - The Result: Instead of a dry, crumbly bark, you get a "glassy" bark—a translucent, mahogany crust that has a deep, jammy chew. 3. The Acid-Sugar-Lipid Balance Barbecue is fundamentally a heavy, fatty (lipid-rich) food. Jam introduces two things that fat needs to taste balanced: Sugar and Organic Acids (like citric or malic acid from the fruit). - Using a Peach Preserve on pork or an Apricot Jam on chicken provides a sharp acidity that "cuts" through the grease, making the meat feel lighter on the palate even though it’s incredibly rich. How to Execute the "Preserve Base" Using jam requires a slight adjustment to your fire management to avoid a "sugar burn." - The Thinning Strategy: Straight jam is too thick and will clump. Whisk your jam with a tablespoon of apple cider vinegar or bourbon to loosen the viscosity. You want a "glaze" consistency, not a "toast" consistency.

2

0

The "Sticky" Science: Why your Rib Glaze is Burning (and how to fix it)

Most people "braai" with sauce. They brush it on cold, it drips into the fire, and it burns into a bitter, black mess. In professional Low & Slow BBQ, we don't "sauce"—we Glaze. If you want that high-gloss, finger-sticking finish on your Beef Plate rib, you need to understand the thermodynamics of sugar. 1. The Maillard vs. Caramelization Trap Your beef rib has been cooking at 110°C to achieve the Maillard reaction (savory browning). But most "sticky" sauces are loaded with sugar or honey. Sugar doesn't caramelize until it hits 160°C. If you apply sauce too early, it just sits there, making your bark "mushy." If the pit gets too hot, the sugar bypasses caramelization and goes straight to carbonization (burning). 2. The "Setting" Phase A professional glaze is applied in the final 20 to 30 minutes of the cook. This is called "Setting the Sauce." You want the heat of the smoker to evaporate the water in the sauce, leaving behind a tacky, concentrated lacquer that bonds to the bark. 3. The Umami-Acid Balance (The S.A. Profile) Beef is incredibly rich. A "sweet" sauce alone is a mistake. To cut through that heavy tallow, your glaze needs: - Acidity: Apple Cider Vinegar or local Lemon juice to "brighten" the fat. - Umami: A splash of Worcestershire sauce or soy sauce to bridge the gap between the sugar and the beef. - The "Stick" Factor: Honey or Apricot Jam (a South African favorite) provides the viscosity needed to "cling" to the rib without running off.

Mastering Beef rib

If you’ve ever tucked into a beef rib and found it "stringy" or hard to chew, it’s not because you bought bad meat. It’s because you missed the Thermal Transition. Here are the three non-negotiables for a world-class "Platrib": 1. The 160°F (71°C) "Melting Point" Beef ribs are packed with Type I Collagen. Unlike a steak, which is tender at $55°C$, collagen doesn't even begin to break down until it hits the 70°C mark. This is "The Stall." If you rush the heat here, the muscle fibers tighten and squeeze out all the moisture. You have to stay patient at 110°C pit temp to allow that collagen to transform into Gelatin. 2. Bark Architecture (The 16-Mesh Secret) Ever wonder why pro BBQ has that dark, "craggy" crust? It’s not burnt; it’s the Maillard Reaction combined with pepper granulation. Using standard table pepper is a mistake—it’s too fine. We use 16-Mesh Coarse Black Pepper. These larger grains create "turbulence" in the airflow, allowing smoke particles to stick to the meat. No coarse pepper = no authentic Texas bark. 3. The "Rest" is a Chemical Process Slicing a rib the moment it comes off the coals is the fastest way to ruin a 9-hour cook. At 95°C, the internal juices are highly pressurized. A 2-hour controlled rest in an insulated cooler allows those juices to thicken and redistribute. This is how you get a rib that stays glistening wet on the cutting board instead of a puddle of liquid and dry meat.

9

0

Reverse Sear: The perfect Gradient

For decades, the "standard" way to cook a thick steak was to sear it over high heat first to "lock in the juices" and then finish it in the oven. Science has since proven that searing does not lock in juices—in fact, the high heat of an initial sear can actually cause the surface fibers to contract so violently that they squeeze moisture out before the middle even gets warm. Enter the Reverse Sear. This technique flips the script by starting low and slow and finishing with a high-heat flash. It is the most scientifically sound way to cook any piece of meat thicker than 1.5 inches. 1. The Myth of the Seal The idea that searing creates a moisture-proof barrier is one of the most persistent myths in the culinary world. If you watch a steak as it sears, you’ll hear a sizzle; that sizzle is the sound of moisture escaping and hitting the hot pan. Searing is about flavor, not hydration. It triggers the Maillard reaction, where amino acids and sugars transform into hundreds of new, savory flavor compounds. 2. The Temperature Gradient Problem When you drop a cold steak onto a 260C grill, you create a massive temperature gradient. By the time the center reaches a perfect medium-rare 57C, the meat just below the surface is likely 93C, leaving you with a thick, gray, overcooked "band" around a small pink center. In a Reverse Sear, by warming the meat at a low temperature 107C first, you ensure the entire steak rises in temperature uniformly. This results in "wall-to-wall" pink meat with almost no overcooked gray band. 3. Surface Dehydration: The Key to the Crust The Maillard reaction cannot happen effectively until surface moisture has evaporated. Water boils at 100C, while the Maillard reaction really kicks into gear above 149C. In a traditional sear, the heat of the pan has to spend energy "boiling off" the surface moisture before it can start browning the meat. In a Reverse Sear, the 45–60 minutes the steak spends in the low-temp oven or smoker acts as a dehydration chamber. By the time you are ready to sear, the surface of the meat is bone-dry.

The holy grail of thin blue smoke

In the barbecue world, we talk about "Thin Blue Smoke" (TBS) with almost religious reverence. Every beginner starts by thinking that "more smoke equals more flavor," but they quickly learn the bitter truth: thick white smoke is the enemy of good food. To understand why, we have to look at the chemistry of combustion. Smoke isn't just one thing; it is a complex mixture of solids, air-borne liquids, and gases that changes based on the temperature of your fire. The Spectrum of Smoke The color of your smoke is a real-time report on how efficiently your fire is burning. - White Smoke: This is the result of "incomplete combustion." It is filled with large particulates, water vapor, and unburnt fuel. It contains high levels of creosote, which creates a bitter, medicinal, and "numbing" sensation on the tongue. If your smoker looks like a steam engine, your meat will taste like an ashtray. - Black/Grey Smoke: This is the most dangerous. It indicates a fire that is "choked"—meaning it has fuel and heat but is starving for oxygen. This produces soot and heavy carbon that will ruin meat instantly. - Thin Blue Smoke: This is the "Sweet Spot." It occurs when the fire is hot enough and has enough oxygen to burn off the heavy, bitter compounds, leaving behind only the microscopic "flavor molecules" like guaiacol (smokiness) and syringol (spiciness). Why is it Blue? (The Rayleigh Scattering Effect) The smoke appears blue for the same reason the sky does—a phenomenon called Rayleigh Scattering. When a fire is burning at peak efficiency (usually between 650 Fahrenheit and 800 Fahrenheit at the coal bed), the particles it releases are incredibly small—smaller than the wavelength of visible light. These tiny particles scatter the shorter (blue) wavelengths of light more effectively than the longer (red) wavelengths. If you see blue, it means your particles are microscopic. If the smoke turns white, the particles have clumped together into larger masses that will land on your meat and create "dirty" flavor.

9

0

1-19 of 19

powered by

skool.com/bbq-beer-and-whiskey-9787

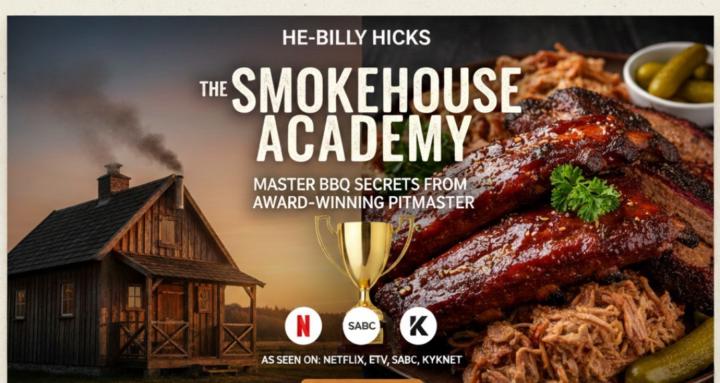

Award-winning pitmaster teaching BBQ, craft beer & whiskey-making. Join He-Billy Hicks' community of makers. Level up your craft. As seen on tv

Suggested communities

Powered by